A young girl in 18th-century Boston memorizes verses in secret, aware that her words could cost her freedom. A woman in a white dress refuses to rise in church because she will not lie about her belief. A contemporary poet stands at a presidential podium, carrying centuries of silenced voices into the national consciousness.

These moments do not belong to separate histories. They form a single, unfinished lineage. Women Poets in US History and Present have always written against erasure, using language as survival and reclamation. Yet despite shaping American literature at its most critical moments, their contributions still fight for equal recognition.

This exploration traces that lineage through twelve women whose poetry reshaped how America understands identity, grief, power, and freedom. Right from enslavement to modern laureateship, Women Poets in US reveal how poetry becomes most dangerous and most necessary.

12 Women Poets in US History and Present Shaped American Literature

To curate this lineup of women poets in US history and present, the focus stays on impact rather than hype. Each poet earned a place here through a combination of historical influence, literary innovation, major recognitions (such as the Pulitzer Prize or U.S. Poet Laureate appointments), and lasting cultural resonance in classrooms, movements, and readers’ lives.

They appear in order of age, from the earliest trailblazers to contemporary voices, showing how women poets in US built a continuous lineage of resistance, experimentation, and emotional truth, rather than isolated moments of “genius.”

1. Phillis Wheatley (1753–1784): The First Voice

Phillis Wheatley’s trajectory defies the boundaries that slavery imposed. Forcibly transported from West Africa at approximately seven years old, Wheatley taught herself to read and write, becoming the first African American to publish a book of poetry. Her 1773 collection stands as a remarkable achievement, not merely for its technical mastery but for its strategic brilliance in advocating for Black inclusion in the Christian movement.

In her most powerful work, “On Being Brought from Africa to America,” Wheatley directly addresses white religious leaders: “Remember, Christians, Negroes, black as Cain, / May be refin’d and join th’ angelic train.” This poem uses the language of her oppressors against them, insisting on the spiritual equality of enslaved people. Tragically, Wheatley died in poverty at age 31, her contributions buried for generations. Today, scholars recognize her not as a curiosity but as a foundational figure whose poetry advanced the anti-slavery movement and validated Black intellectual capacity during an era determined to deny it.

2. Emily Dickinson (1830–1886): The Recluse Who Revolutionized Form

Emily Dickinson transforms our understanding of what poetry could be. Working in isolation in Amherst, Massachusetts, Dickinson produced nearly 1,800 poems that shattered 19th-century conventions with dashes, slant rhymes, and fragmentary lines that forced readers to pause, question, and contemplate meaning beyond surface language.

Dickinson’s brilliance extended beyond form into intellectual rigor. She challenged scientific materialism, expressing skepticism about reducing nature to mere data collection. In one poem, she writes: “A monster with a glass / Computes the stamens in a breath – / And has her in a ‘class!’” This critique anticipated contemporary feminist science studies’ arguments about the dangers of dehumanized objectification.

Her religious skepticism also proved revolutionary. When asked to affirm Christian conversion at Mount Holyoke Women’s Seminary, Dickinson remained seated while others stood. She later explained she could not lie about her convictions. This integrity shaped her poetry about faith, doubt, and mortality; poems that gain new readers every generation because they articulate timeless human uncertainties with unprecedented artistry.

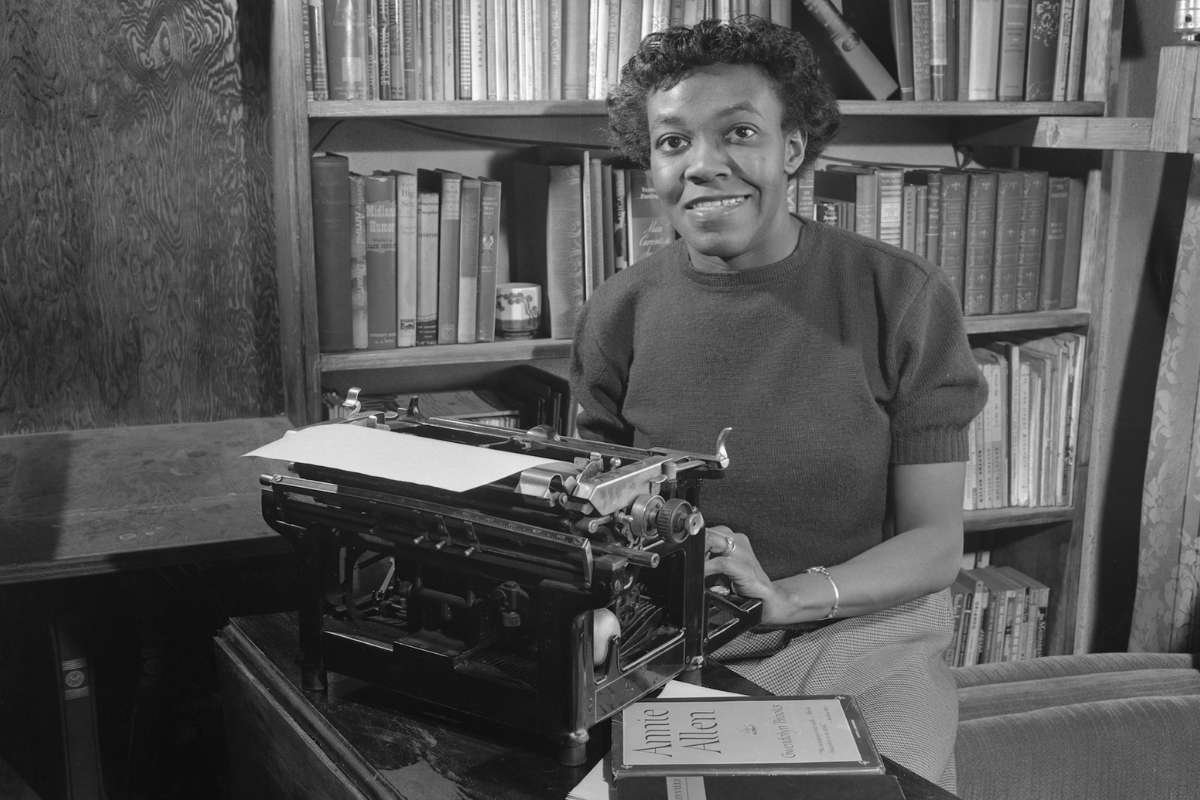

3. Gwendolyn Brooks (1917–2000): Poetry as Political Action

Gwendolyn Brooks made history on May 1, 1950, when she became the first African American to win the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry for her collection “Annie Allen.” This achievement shattered the gatekeeping structures of American literary institutions, yet Brooks’s significance extends far beyond breaking barriers, while her poetry centers the lived experiences of ordinary Black people, particularly women and children navigating systemic racism.

Beginning at age 17, Brooks published regularly in the Chicago Defender, an anti-racism newspaper serving Chicago’s Black community. Her landmark collection “A Street in Bronzeville” (1945) portrayed the complex interior lives of poor, urban Black residents with unprecedented dignity and nuance. Notably, Brooks refused to ignore colorism within Black communities, a radical gesture when many sought to present unified racial narratives. Critic Annette Oliver Shands observed that Brooks’s works “assert humanness with urgency.”

In 1969, Brooks made another revolutionary decision: she left Harper & Row, her white mainstream publisher, to work with Black-owned publishing companies. This choice of choosing her community’s autonomy over institutional prestige redefined what poetry could accomplish as an act of resistance and solidarity. Brooks later served as the Poet Laureate of Illinois, ensuring her legacy centered the voices that publishing houses had systematically excluded.

4. Anne Sexton (1928–1974): Confessional Courage

Anne Sexton’s poetry reads like testimony from a witness forced into uncomfortable silence. Born Anne Gray Harvey in Newton, Massachusetts, Sexton experienced severe bipolar disorder beginning in her twenties. Rather than hide this reality, she transformed her psychiatric treatment and therapy sessions into poetry that shocked 1950s sensibilities with its brutal honesty about women’s inner lives.

In 1953, Sexton experienced her second manic episode and met Dr. Martin Orne, the therapist who would encourage her to write poetry as a form of psychological healing. Later, studying with renowned poet Robert Lowell at Boston University alongside Sylvia Plath and George Starbuck, Sexton found her voice. Her 1967 Pulitzer Prize-winning collection “Live or Die” explores suicide, addiction, and the suffocating constraints of marriage and motherhood with unflinching directness.

Sexton’s friendship with Plath deepened following Plath’s 1963 suicide. In response, Sexton wrote “Sylvia’s Death,” an elegy that transforms personal grief into collective witness. By naming her friend’s death, addressing Plath’s haunting power over her own imagination, Sexton refused the feminine silence that would have been culturally expected. Her openness about mental illness and suicidal ideation offered lifelines to countless readers experiencing similar struggles in isolation.

5. Maya Angelou (1928–2014): The Poet of Resilience and Justice

Maya Angelou’s story embodies transformative power. Traumatized by sexual assault in childhood, Angelou remained mute for five years, an experience she would later transform into profound artistic and activist work. Her love of language propelled her beyond trauma into a career spanning poetry, memoir, education, and civil rights activism that inspired generations.

After hearing Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. speak at the Harlem Writers Guild in the late 1950s, Angelou committed to the civil rights movement, working directly with Dr. King and Malcolm X. In 1993, Angelou made history as the inaugural poet for President Bill Clinton’s inauguration, reading her poem “On the Pulse of Morning.” This poem echoed King’s call for peace, acceptance, and racial justice to an estimated 100 million viewers, poetry reaching audiences no academic journal could match.

Angelou’s memoir “I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings” (1969) revolutionized American literature through its courageous discussion of sexual abuse. By centering her own survival and self-recovery, Angelou validated countless readers’ experiences while insisting that broken people possessed dignity and power. Her trajectory from silence to the presidential inaugural platform demonstrates poetry’s capacity to heal personal trauma while advancing collective liberation.

The Artistry and Impact of Women in Literature and Film

Explore the remarkable influence of women in literature and film, their artistic contributions, and societal impact in this insightful exploration.

6. Sylvia Plath (1932–1963): The Architecture of Suffering

Sylvia Plath’s death by suicide at age 30 crystallized her significance as a cultural symbol, yet reducing her legacy to tragic melodrama obscures her revolutionary contributions to poetry. Plath pioneered confessional poetry alongside Sexton and Lowell, but her work achieved unprecedented intensity through metaphorical architecture that transforms personal breakdown into universal human struggle.

Her novel “The Bell Jar” (1961), published just months before her death, depicts a young woman’s mental collapse with novelistic specificity. Yet Plath’s poetry achieves something the novel cannot: the distillation of complex emotional states into crystalline language. Her posthumously published collection “Ariel” (1965) contains poems like “Daddy” and “Lady Lazarus” that explore power, resurrection, and the brutal costs of patriarchal constriction with unprecedented rawness.

In 1982, two decades after her death, Plath received the Pulitzer Prize for “The Collected Poems.” This posthumous recognition infuriated some who felt Plath’s suicide had been instrumentalized. Yet the prize acknowledged a crucial reality: Plath’s suffering generated art of transcendent power that spoke to the feminist movement’s core arguments about how patriarchy damages women’s psychological and creative lives. Critics like Charles Newman wrote that her literature “gives us one of the few sympathetic portraits of what happens to one who has genuinely feminist aspirations in our society.”

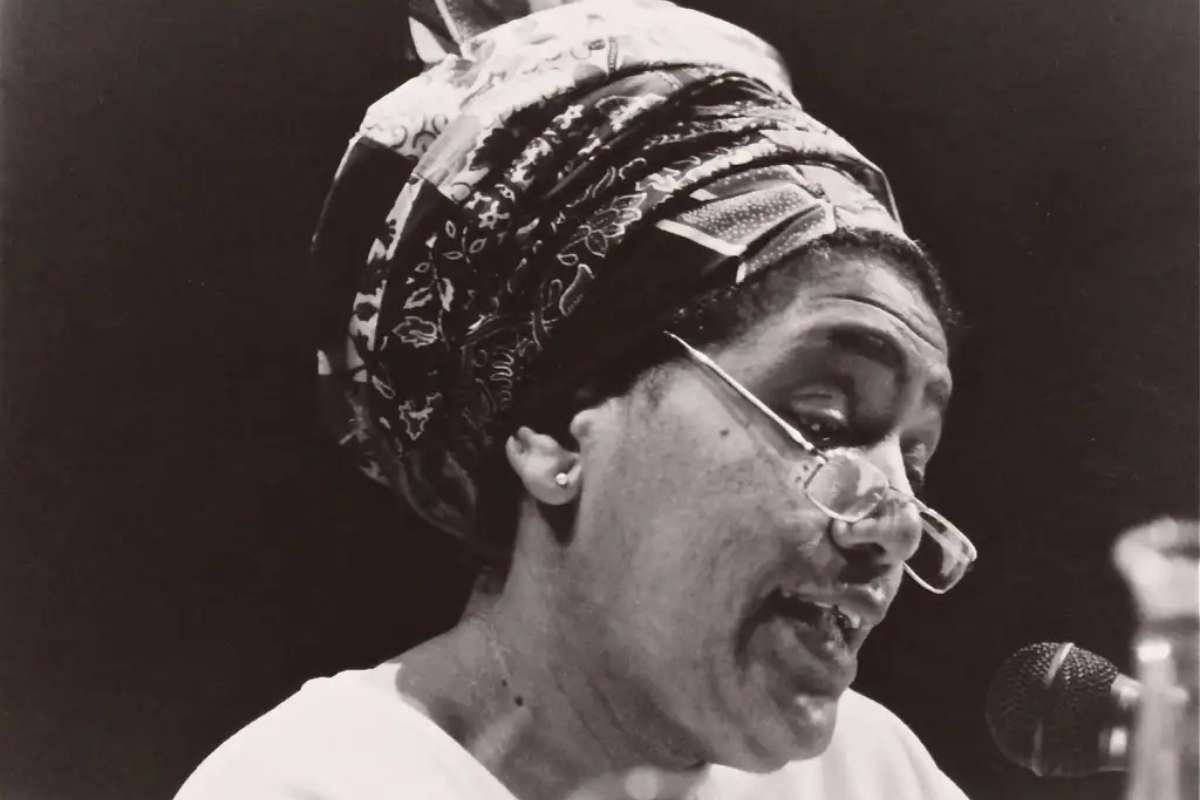

7. Audre Lorde (1934–1992): The Black Lesbian Warrior Poet

Audre Lorde described herself simply: “Black, lesbian, feminist, socialist, mother, warrior, and poet.” This self-definition rejected the singular identity categories that institutions preferred, instead asserting the simultaneity of her identities and commitments. As a poet and theorist, Lorde pioneered intersectionality, the recognition that oppressions interconnect and that liberation movements must address racism, homophobia, classism, and sexism simultaneously.

Lorde’s poetry embodies what she termed the “uses of the erotic,” the political power of feeling, passion, and embodied truth-telling. In her essay “The Uses of the Erotic as Power,” Lorde argues that patriarchy suppresses women’s capacity for deep feeling because emotion generates resistance. Her poetry channels this dangerous emotion, expressing anger at injustice with technical brilliance and moral clarity.

In 1981, Lorde co-founded Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press with Cherríe Moraga and Barbara Smith, a publishing enterprise dedicated to amplifying Black feminist voices. Additionally, Lorde publicly rejected the expectation that she wear a prosthesis after her 1978 mastectomy. In doing so, she insisted: “If we are to translate the silence surrounding breast cancer into language and action against this scourge, then the first step is that women with mastectomies must become visible to each other.” This stance transformed how cancer survivors approached their bodies and identities.

8. Lucille Clifton (1936–2010): The Power of Brevity

Lucille Clifton possessed an extraordinary ability to say infinitely much within concise language. Born in Depew, New York, Clifton’s poetry celebrates African American family life, female embodiment, and spiritual resilience with deceptive simplicity. Her collection “Blessing the Boats” (2000) won the National Book Award, recognizing her lifetime achievement in creating poems of crystalline power.

Clifton’s poem “Homage to my hips” exemplifies her approach, a brief celebration of female sexuality and self-love that subverts centuries of male-centered body criticism. Another celebrated work, “poem in praise of menstruation,” transforms a biological process typically coded as shameful into something worthy of reverence. By writing these poems, Clifton claimed space for women’s bodily autonomy and pleasure within the literary tradition.

Clifton’s technical mastery reveals itself in her refusal of capitalization and punctuation, choices that create emotional directness and intimacy. Her work influenced an entire generation of poets to reconsider formal conventions, demonstrating that minimalism could generate maximum emotional and political impact. Elected Chancellor of the Academy of American Poets in 1999, Clifton used her platform to advocate for poetry’s accessibility and its connection to lived experience.

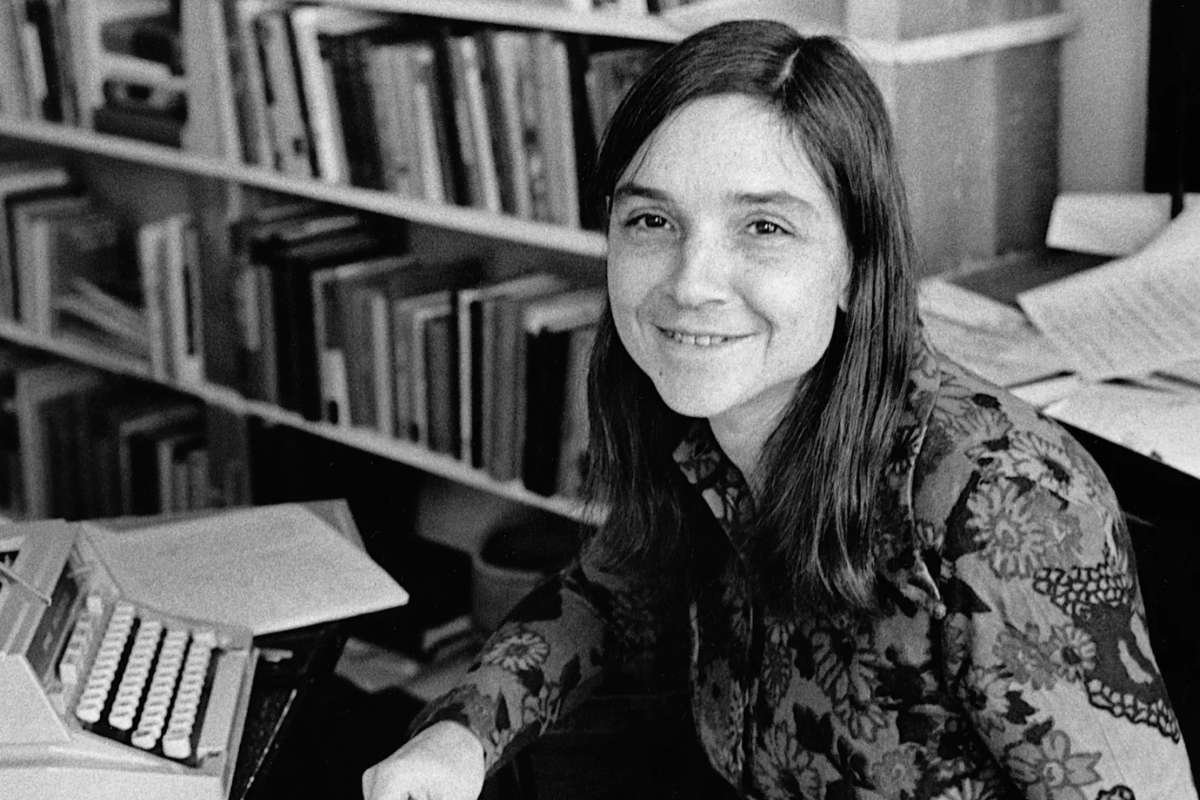

9. Adrienne Rich (1929–2012): Poetry as Political Refusal

Adrienne Rich’s career trajectory demonstrates how a poet evolves from acclaimed formalist to radical interrogator of systems that produce poetry itself. Her early work received prestigious recognition, yet Rich grew increasingly critical of the literary establishment she inhabited. By the 1960s, Rich had begun interrogating her own complicity in patriarchal literary traditions.

In “Snapshots of a Daughter-in-Law” (1963) and “Of Woman Born” (1976), Rich articulated the subjugation embedded in idealized motherhood, arguing that patriarchy had colonized women’s reproductive capacity. Her collection “Twenty-One Love Poems” (1977) and “Dream of a Common Language” (1978) explicitly represented lesbian sexuality and desire, a move that challenged heteronormative literary conventions and validated queer women’s experiences as worthy of serious artistic attention.

Rich’s political activism extended beyond poetry. In 1968, she signed the “Writers and Editors War Tax Protest,” pledging to refuse taxes in opposition to the Vietnam War. Then, in 1997, she declined the National Medal of Arts to protest House Speaker Newt Gingrich’s vote to defund the National Endowment for the Arts. Like Audre Lorde, Rich insisted that personal literary achievement meant little without solidarity with communities facing systemic oppression. Her essay collection “Blood, Bread, and Poetry” remains essential reading for anyone seeking to understand how feminist poets connected their art to larger movements for social transformation.

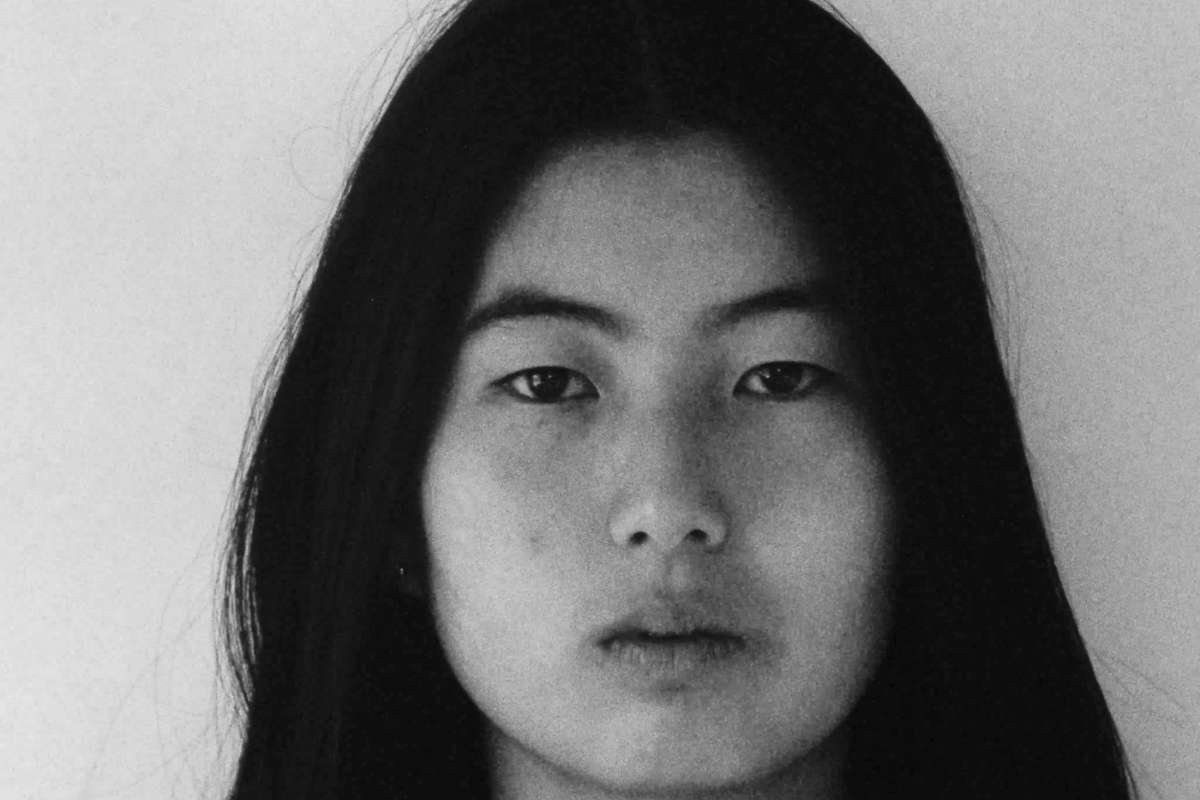

10. Theresa Hak Kyung Cha (1951–1982): Experimental Forms, Transnational Memory

Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s career lasted only a decade before her violent death in 1982, yet her major work, “Dictée,” achieved legendary status precisely for its formal experimentation and its engagement with transnational trauma. Born to Korean parents, Cha grew up in Hawaii, the Philippines, and finally San Francisco, making her consciousness inherently diasporic.

“Dictée” resists generic classification, combining poetry, prose, visual art, and historical documentation to represent the traumatic experiences of Korean colonization, Japanese occupation, and diaspora. Cha centers courageous women within this historical narrative: the Korean revolutionary Yu Guan Soon, Joan of Arc, Saint Thérèse, and Cha’s own mother. By weaving these women’s stories together, Cha creates what theorists call “transnational feminism,” a framework recognizing that women’s liberation must address colonial violence, nationalist movements, and family trauma simultaneously.

The New York Times recognized “Dictée” as a significant literary achievement, a validation that experimental, formally challenging work by poets of color could command serious critical attention. Although Cha died tragically, her influence on contemporary women poets in US history and present remains profound, demonstrating that formal innovation and political urgency need not be opposing forces.

11. Joy Harjo (1951–present): Indigenous Poetry, Sacred Language

Joy Harjo’s appointment as U.S. Poet Laureate in 2019 made her the first Indigenous person to hold this position, a historic recognition of poetry traditions colonized nations have practiced for centuries. Member of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation, Harjo’s work explores the injustices committed against Indigenous peoples while recovering spiritual and cultural values threatened by colonialism.

Harjo’s poem “She Had Some Horses” demonstrates her psychological sophistication. Rather than depicting unified identity, the poem explores internal contradiction, the coexistence of opposing forces within human consciousness. This represents a fundamentally different approach to selfhood than the Western individualism that dominates American literature. Harjo writes toward wholeness that embraces multiplicity rather than resolving contradictions.

In collections like “In Mad Love and War” (1990), Harjo memorialized Indigenous leaders and lamented the violence colonialism perpetuates. Poet Adrienne Rich observed of Harjo’s work: “I turn and return to Harjo’s poetry for her breathtaking complex witness and for her world-remaking language: precise, unsentimental, miraculous.” This description captures what distinguishes Harjo’s achievement; she combines technical precision with visionary expansiveness, making space for Indigenous epistemologies within American literary institutions while maintaining critical distance from those institutions’ limitations.

12. Rita Dove (1952–present): Music, History, and Lyric Beauty

Rita Dove made history in 1993 when, at age 40, she became the youngest person and first African American appointed U.S. Poet Laureate. This achievement came after winning the Pulitzer Prize in 1987 for “Thomas and Beulah,” a collection telling her grandparents’ story through interconnected poems exploring family, love, and the African American experience across generations.

Dove’s technical mastery combines with thematic ambition in ways that elevate personal narrative into cultural significance. A trained cellist, Dove incorporates musical structures and themes into her poetry, creating rhythms that mirror the jazz and blues traditions central to African American cultural expression. Her poems demonstrate that formal beauty and political significance need not conflict; indeed, they reinforce each other.

During her tenure as Poet Laureate (1993–1995), Dove expanded the position’s cultural reach, advocating for poetry’s accessibility and relevance to diverse audiences. She served as Chancellor of the Academy of American Poets from 2005 to 2012, using institutional positions to advance younger poets, particularly writers of color. In 2021, Dove received the gold medal in poetry from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, only the third woman and first African American to receive this honor in the award’s 110-year history.

Contemporary Voices: Women Poets in US History and Present Continuing the Revolution

The achievement of women poets in US history and present extends into the present moment with remarkable force. Ada Limón currently serves as U.S. Poet Laureate and was the first Latina woman to hold the position. Her collection “The Carrying” (2018) won the National Book Critics Circle Award and explores grief, infertility, and caregiving with unflinching honesty. Vanity Fair praised her “keen attention to the natural world” combined with “incredible emotional honesty.”

Natalie Diaz, a Mojave poet born in 1978, won the 2021 Pulitzer Prize for Poetry for “Postcolonial Love Poem.” Her work explores what it means to love in an America “beset by conflict,” with particular attention to Indigenous experiences and queer desire. The Pulitzer committee called her collection “a collection of tender, heart-wrenching and defiant poems,” affirming that contemporary women poets in US history and present continue advancing the field’s boundaries.

Claudia Rankine’s book “Citizen: An American Lyric” (2014) achieved unprecedented recognition, becoming the first poetry book in National Book Critics Circle history to be nominated in both poetry and criticism categories. Her work combines visual art, historical documentation, and lyric language to chronicle racial violence and microaggressions in contemporary America. Rankine received the MacArthur Fellowship in 2016, recognizing her innovative contributions to literature and cultural criticism.

Danez Smith, a queer, non-binary poet from St. Paul, Minnesota, represents a new generation of women poets in US history and present, bringing experimental form and radical vulnerability to contemporary poetry. Smith’s collection “Don’t Call Us Dead” (2017) was a finalist for the National Book Award and demonstrates Smith’s capacity to write about death, desire, and community with devastating honesty. Their poetry slam achievements and cultural criticism work establish poetry as a living practice inseparable from activism and community-building.

The Statistical Reality: Persistence and Progress

Statistics reveal both progress and persistent inequality in recognizing women poets in US history and the present. The 2017 Survey of Public Participation in the Arts showed women’s poetry reading increased dramatically, from 8.0% in 2012 to 14.5% in 2017. Women continue to account for over 60% of all poetry readers, yet remain significantly underrepresented among Pulitzer Prize winners.

Women have won the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry only 29 times out of 91 total awards, approximately 32 percent. Remarkably, the 1950s saw an entire decade pass with no women Pulitzer recipients, though the jury’s 1957 recommendation for Elizabeth Spencer was rejected by the board. This historical erasure demonstrates how institutional gatekeeping functions even when women produce excellence.

The 2020 Nobel Prize in Literature went to Louise Glück, marking her distinction as the first American woman to win this supreme international honor in 27 years. The Swedish Academy praised her “unmistakable poetic voice that with austere beauty makes individual existence universal.” Glück’s achievement represents vindication for women poets whose work had long deserved such international recognition.

Conclusion

The girl writing in secret, the recluse refusing false faith, the poet addressing a nation—these figures no longer stand alone. They echo through classrooms, libraries, protests, and private moments of recognition when a reader sees herself reflected in a line of verse.

Women Poets in US History and Present did more than expand American literature. They rewired it. They forced the canon to confront whose voices matter, whose pain counts as history, and whose joy deserves preservation. Their work proves that poetry does not merely observe culture; it reshapes it.

As readers, our role remains unfinished. To read these poets is to refuse erasure. To teach them is to correct history. To celebrate them is to acknowledge that Women Poets in US are not footnotes to American literature; they are its backbone, its conscience, and its future.

Thank You for Reading!

Learn More

Empower Your Mind With 15 Podcasts That Will Make You A Smarter Human