To better the utility and beauty of urban public space, urban design aims to improve the livability and accessibility of cities. A controversial trend in urban design called Anti-Homeless Architecture has started to emerge, and this has attracted a lot of discussion. This concept has taken the form of features such as spikes, segmented benches, and sloped spaces designed to deter homeless individuals from resting or using them as shelter in places where, in a city, a person may have the right to use.

Supporters of anti-homeless architecture argue that this can keep spaces within cities clean and orderly. Critics state that this is one of the more overt forms of social exclusion and systemic discrimination. Cities are facing greater rates of homelessness and it is important to understand what this trend in urban planning means.

What is Anti-Homeless Architecture?

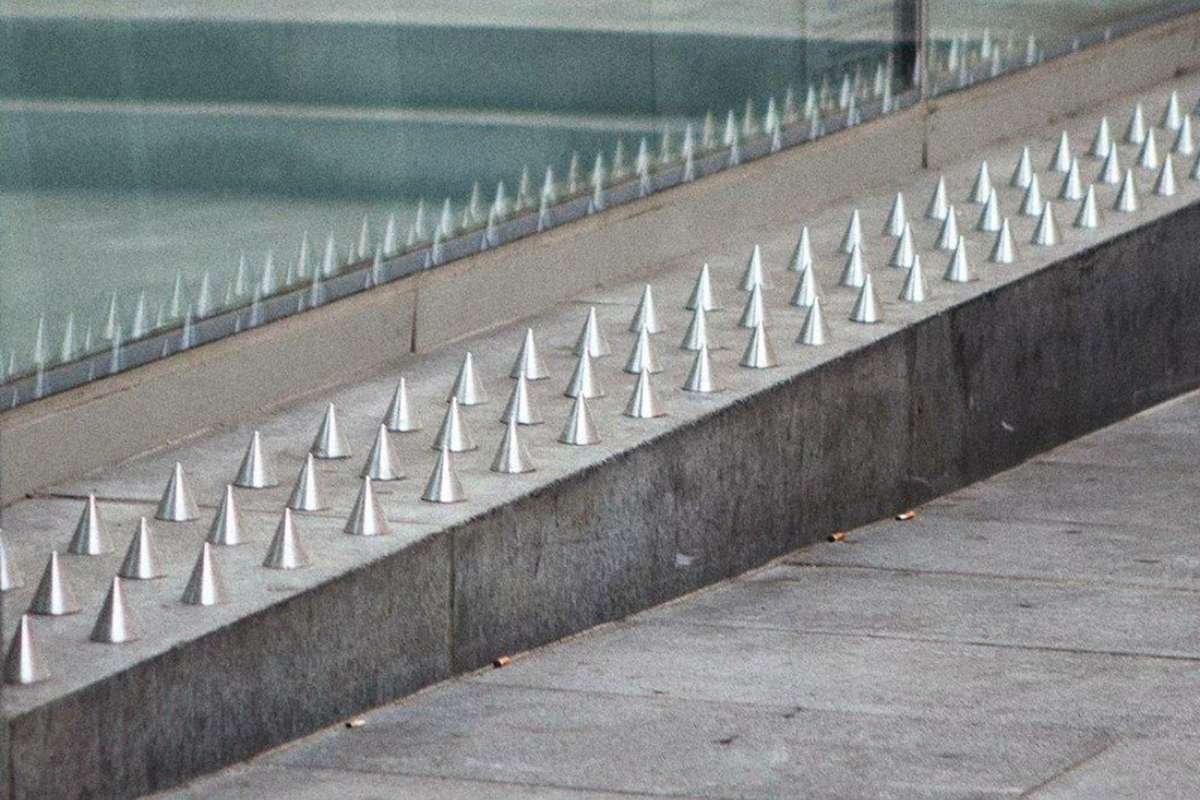

Anti-Homeless Architecture, also called hostile architecture or defensive design, refers to urban design strategies intended to restrict certain behaviors in public spaces, particularly those of homeless individuals. Some common examples include:

- Bench dividers that make lying down impossible

- Slanted or curved seating to discourage prolonged sitting

- Spiked ledges on flat surfaces

- Gated doorways and underpasses to prevent encampments

- Sprinkler systems are timed to go off randomly to deter sleeping

While these features are often installed under the guise of deterring loitering or vandalism, the underlying objective is frequently to make spaces uninhabitable for the homeless.

The Rise of Anti-Homeless Architecture

This form of design has gained popularity in many global cities, from London and Paris to New York and Mumbai. Often implemented without public consultation, these features are introduced quietly and marketed as urban enhancements.

Local governments and businesses sometimes defend such practices by stating that they’re trying to reduce crime or maintain commercial appeal. However, critics argue that Anti-Homeless Architecture is not a solution but a deflection — an attempt to hide homelessness instead of addressing its root causes.

In 2025, with inflation, housing shortages, and economic instability persisting, homelessness remains a major urban issue. Yet, resources are increasingly diverted toward exclusionary design instead of support services.

Ethical and Humanitarian Concerns

One of the most serious criticisms of Anti-Homeless Architecture is its ethical implications. Rather than helping individuals in need, it actively works to push them out of sight. This promotes a “not in my backyard” mentality, dehumanizing people who are already marginalized.

Key ethical concerns include:

- Violation of human dignity: Everyone deserves access to safe and humane public spaces.

- Neglect of social responsibility: It shifts the burden of homelessness away from policymakers and onto individuals.

- Invisible punishment: It criminalizes poverty without legal recourse or due process.

Urban spaces should be inclusive and welcoming, but hostile design intentionally excludes the most vulnerable, reinforcing cycles of poverty and isolation.

Legal and Policy Backlash

The increasing visibility of anti-homeless architecture has triggered legal and political responses. Several cities and countries are now questioning its legality under human rights laws. For example:

- In 2023, the Los Angeles City Council passed a motion to evaluate all public architecture for signs of hostile design.

- Canada’s Charter of Rights and Freedoms has been cited in court cases arguing that defensive architecture violates basic freedoms.

- The United Nations Human Rights Council has condemned hostile urban design as “cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment.”

There’s also a growing movement among urban planners and architects advocating for inclusive design, public spaces that serve all members of society, including the homeless.

Social Alternatives to Hostile Design

Instead of investing in exclusionary structures, urban planners can implement positive solutions that address homelessness more constructively:

- Housing-first initiatives: Prioritize providing permanent housing as a basic right.

- Public shelters and day centers: Offer spaces where unhoused individuals can safely rest and access essential services.

- Community benches and pods: Design urban furniture that accommodates both public use and emergency shelter.

- Social programs: Invest in mental health, addiction services, and employment support for homeless populations.

By redirecting resources from Anti-Homeless Architecture to humane interventions, cities can work toward sustainable, long-term solutions.

Public Perception and Activism

Public sentiment toward anti-homeless architecture is changing. Social media campaigns have called out businesses and municipalities for installing such features. Hashtags like #HostileDesign and #DesignForAll have fueled global awareness.

Artists and activists are also fighting back creatively. Some examples include:

- Placing mattresses and pillows on spiked surfaces to highlight their cruelty

- Launching petitions to remove hostile installations

- Creating interactive exhibits that simulate the experience of homelessness

These grassroots efforts are shifting the narrative, making people question who urban spaces are truly for and inspiring demand for inclusive urban design.

The Way Forward

Combating homelessness requires compassion, funding, and systemic change, not simply hiding the problem behind sloped benches and metal spikes. Governments, urban planners, and citizens must work together to rethink public space design.

Key action points include:

- Audit all urban spaces for hostile features and reassess their necessity

- Engage with homeless communities in planning public spaces

- Educate the public on the impact of exclusionary architecture

- Promote inclusive city policies that prioritize dignity, housing, and access

If urban design is a reflection of societal values, then cities filled with hostile architecture send a clear, chilling message: that some lives matter less.

Conclusion

Anti-Homeless Architecture is not simply a design trend; it is a representation of systemic failure. While the visual or commercial gain may feel immediate, it comes with the cost of humanity, equity, and social responsibility.

Urban space should not have to be divisive; it should lift people up. Until urban design embodies this justification, no progress will be made in the flawed conversation about homelessness. It is time to stop accepting hostile architecture as an anti-solution to a humanitarian crisis. It’s time to reject the architecture of hostility and invest in real, human solutions. It’s time to start developing cities for everyone, not just the privileged.