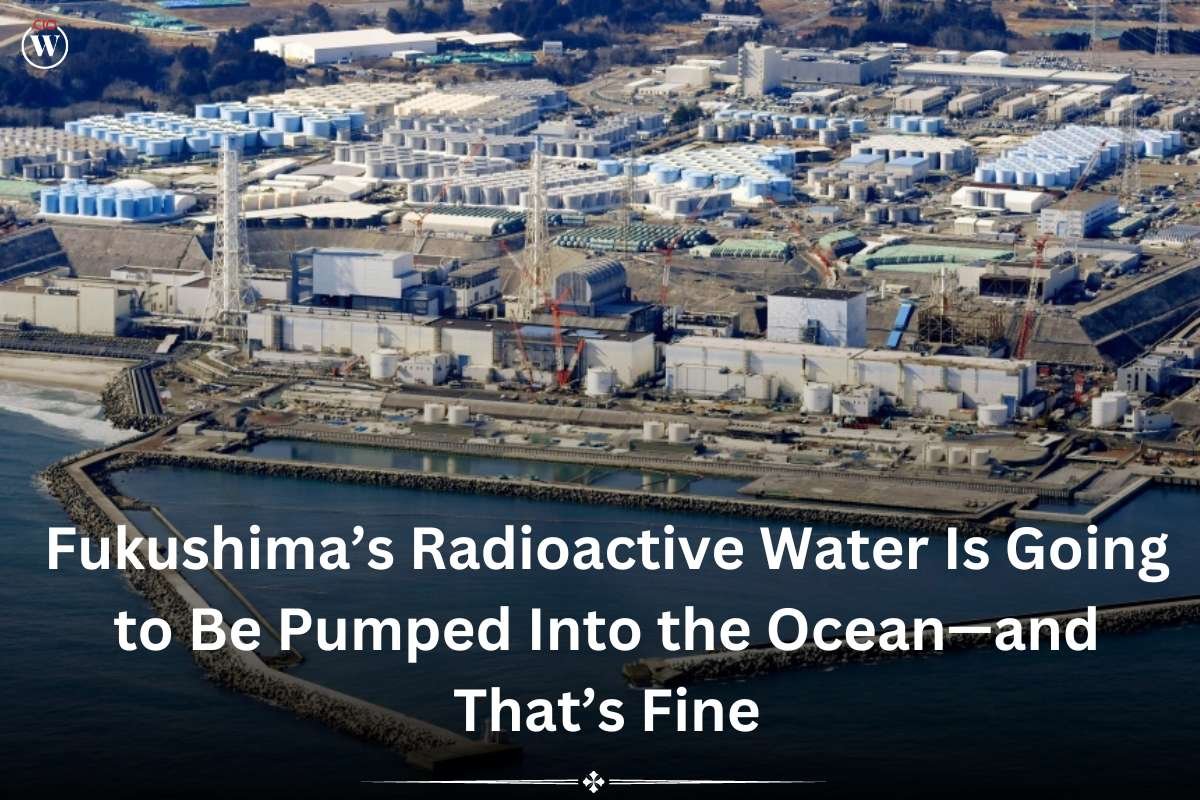

In satellite images, the tanks of radioactive fluid from Japan’s Fukushima nuclear plant resemble the pale blue and gray eggs of a giant butterfly, arranged in orderly patterns as if on a dismal leaf. These tanks, made of steel, are now slated to be diluted and released into the sea. Núria Casacuberta Arola, a researcher from ETH Zürich, is closely monitoring this process.

Casacuberta Arola and her team regularly deploy a device consisting of jars into the waters near the Fukushima nuclear plant to collect water samples at various depths. The jars automatically close one by one as the device is pulled back to the surface. Alongside this, they also take sediment samples from the seabed. Their objective is to study whether the water disposal from Fukushima nuclear plant will lead to a significant rise in radiation levels in the Pacific Ocean’s vicinity in the coming months and years. The water release is anticipated to begin as early as next month, and if a noticeable increase in radiation is observed in the surrounding waters, it could indicate serious issues.

Breaching the defensive sea wall designed to protect the plant

The Fukushima nuclear plant Station was struck by a massive tsunami in 2011, breaching the defensive sea wall designed to protect the plant. This led to flooding and partial meltdowns of reactors, resulting in major explosions and one of the worst nuclear disasters in history. Since then, workers have been continuously pumping water to cool the reactors, but this water has become irradiated and cannot be simply discarded. As a result, a substantial amount of contaminated water, approximately 1.3 million metric tons, has been stored on-site, and there is no more space for additional tanks. Hence, the decision to discharge the water has been made.

After years of research and modeling, the International Atomic Energy Agency and Japan’s Nuclear Regulation Authority have approved the discharge plan. This means the Tokyo Electric Power Co (Tepco), responsible for the plant and its cleanup, has the authority to gradually release the water into the ocean via an underwater pipe that extends 1 kilometer.

Though some local fishermen and South Korean protestors are against the plan, many scientists are confident that the discharge will be safe. Tepco has employed water purification technology to treat the contaminated water before storage, which involves passing it through chambers containing materials that adsorb the radionuclides, reducing the radioactive components to a minimum before discharge. However, the water purification system in place at the Fukushima nuclear plant is not entirely foolproof, and certain radionuclides it aims to remove, like cesium-137 and strontium-90, can still be found in the stored water. Additionally, there are isotopes, such as carbon-14 and tritium, that the system cannot eliminate at all. Tritium, in particular, is a form of hydrogen with two neutrons and one proton in its nucleus, and it is naturally present in our surroundings at low levels, with higher concentrations associated with nuclear-related activities.

Japan’s plan to release Fukushima nuclear plant water into sea

Despite the presence of some radionuclides in the stored water, Jim Smith, a professor of environmental science at the University of Portsmouth, assures that the water is extremely safe due to the remarkably low concentrations of these substances. He expresses confidence in the plan to discharge the water and explains that he is not concerned about any potential environmental impact. Smith draws on his extensive experience studying the effects of radiation near the Chornobyl nuclear power plant, where exposure to radiation is much higher. Even in Chornobyl’s highly irradiated environment, the ecological impact appears minimal. While radiation can cause damage to DNA, the subtle effects at these low levels are unlikely to have a significant impact on the ecosystem, he notes.

Nuclear Facilities Worldwide

It is worth noting that tritium, one of the isotopes unable to be removed from the stored water, is already present naturally in our environment at low levels. Moreover, nuclear facilities worldwide routinely release water containing tritium into the sea, sometimes in larger quantities than what is planned for Fukushima nuclear plant. For example, the Cap de la Hague nuclear processing site in France releases over 13 times the total radioactivity of tritium present in all of Fukushima nuclear plant storage tanks annually.

To prepare for the release of the water, Tepco is conducting regular tests on the stored water. It will be re-treated as needed and diluted more than 100 times to reduce its tritium radioactivity concentration to a level well below Japan’s national safety standards. The water will also undergo additional treatment to bring concentrations of other radionuclides below regulatory limits before being discharged. Stringent testing will be carried out once more before the water is released into the ocean.